To round off an eventful week at The 100% CI — after a series of posts on a Red-Team Challenge featuring our own Ruben (Part I, Part II, Part III) — we are pleased to present yet another guest blog: Leonid Tiokhin was desperate enough willing to let us illustrate the inaugural post of his own blog with signature The 100% CI artwork in order to get it cross-posted on our site. We say it’s a win-win! He says… well anyway, here is his post:

People make mistakes. A friend might promise that she’ll pick you up from the airport, but then accidentally sleep through her alarm. A jury might deliver a “guilty” verdict, even though the accused person is innocent. And a football referee might award a penalty kick for what looked like a serious foul in the box, even though the fouled player just made a convincing dive.

In a world where people make mistakes, it’s nice if there is some mechanism to correct them. Recently, I’ve been thinking about this in the context of academic journal editors making publication decisions, where, in theory, just such a mechanism exists: the appeal.

A stylized version of the publishing process might look something like this. A scientist conducts research, writes it up in a paper, and sends the paper to an academic journal for publication. An editor evaluates the paper and decides to send it out for peer review. The scientist then spends the next few weeks or months (or years :/) refreshing their email inbox, waiting for the editor’s decision. One day, the email arrives: “Decision on your submission to Schmience.”

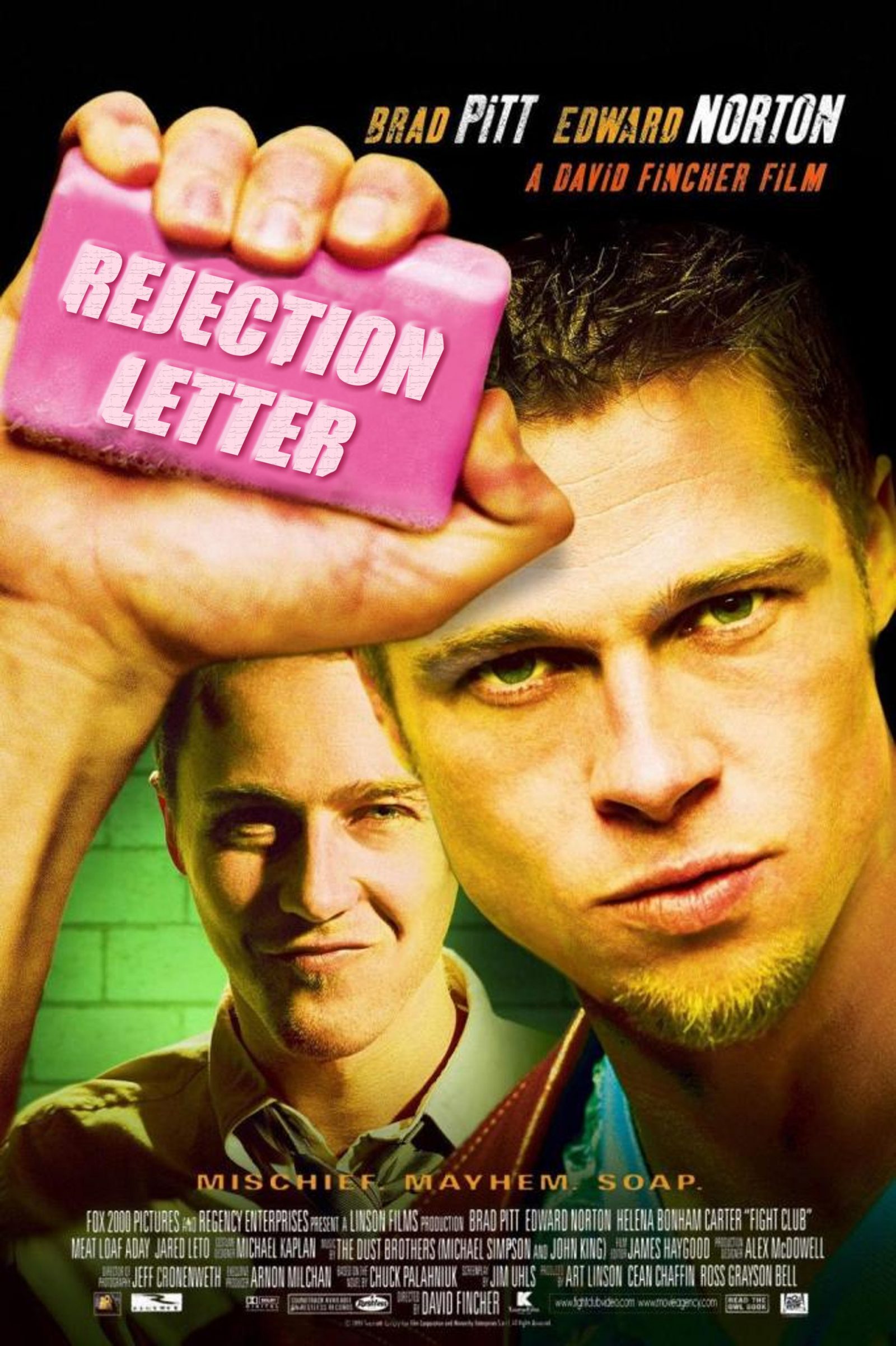

With a mixture of anticipation and dread, the scientist opens the email — click — only to read:

Thank you very much for submitting your manuscript entitled “I spent the last three years working on this” for consideration as an article in Schmience. As with all papers reviewed by the journal, yours was assessed and discussed by the Schmience editors, an Academic Editor with relevant expertise and by independent reviewers. Based on the reviews, I regret that we will not be pursuing this manuscript for publication at Schmience.

We were interested in your study, which took three years of your life. While this analysis will certainly be of interest to those in the field and is well-written, the Academic Editor is not persuaded that it is suitable for Schmience. As you will see from the reviews, the reviewers both value the research question and are positive about some aspects of the manuscript. However, they both have rather fundamental concerns. Reviewer 1 notes that your research does not allow for enlightening results, and they question the assumptions made and their real-life relevance. Reviewer 2 has related concerns regarding some of the assumptions. Given these comments, combined with initial editorial concerns regarding conceptual advance, the team of editors has concluded that the study cannot easily be revised in such a way as to satisfy the reviewers’ concerns and present the strength of insight we must require to meet our rigorous criteria. I am sorry that we cannot be more positive on this occasion.

At this point, what typically happens is that the scientist carefully considers the reviews, realizes that they were fair and constructive, and thanks the editor and reviewers for taking time to evaluate the research. The scientist then takes another few months to improve the paper (often conducting additional research to address the reviewers’ concerns), at which point they resubmit an improved version of the paper to another journal, where the entire process starts anew.

I’m kidding.

What actually happens is that the scientist reads the email, throws coffee all over their laptop, and screams “Fuckkkkkkk, are you kidding me?! These idiots! They didn’t understand the paper at all! Why did I choose this career?!” The scientist then takes some time to cool off and sets the paper aside. Eventually, they come to see that the editor’s and reviewers’ comments had some merit, and revise the paper a bit in response to the reviews. Or maybe they just ignore the comments and resubmit elsewhere. Both things can and do happen.

But that’s not the only way things can go. Technically, the scientist has another tool at their disposal: appealing the editor’s decision. How do such appeals work?

Well, the appeal process in academic publishing is a lot like the process of challenging referee decisions in professional sports. A formal academic governing body, the Board of Global Academic Integrity, laid out the rules for academic appeals over two decades ago. These rules apply to all journals indexed by the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI). For an appeal to be successful, a scientist must provide incontrovertible evidence that the editor and/or reviewers misunderstood or mischaracterized aspects of the paper, and that these misunderstandings render the editor’s decision to reject the paper unjustifiable. The journal has 2 weeks from the date of receiving an appeal to make its decision. To minimize biases, the decision must be made by a different editor than the one who made the initial rejection decision. Scientists are allowed a maximum of two unsuccessful appeals per year. So, if a journal rejects a scientist’s paper, the scientist appeals, and the editor’s decision doesn’t change (e.g., a rejection is not overturned), then the scientist loses one of their appeals for that year. Scientists are penalized for failed appeals — they lose the possibility to submit to the same journal for the next five years. To ensure transparency, the content of all appeals is made public, including the names of the editor and the authors of the paper. These combined measures help to disincentivize scientists from overburdening editors with frequent appeals.

You may be thinking, “hey, cool — scientists have given a lot of thought to this problem, and these measures sound like a reasonable way to deal with it”. And you’d be right. There’s just one small issue. That whole thing about how appeals work? I made it up ( sorry :/ ).

The reality of appeals in academic publishing

The reality is, unlike the transparent, clear guidelines for appeals in the legal system or for challenges in professional sports like tennis, baseball, field hockey, and American football, appeals in academic publishing are like the wild west. There are no rules. There is no transparency. Scientists rarely talk about appeals and receive no formal training about how to handle them. Nobody knows how often appeals occur or what percentage of appeals are justified. Nobody knows which scientists have never appealed and which ones are the assholes who appeal every decision. And readers of papers have no way of knowing whether a paper was only accepted after an appeal. At most, you can find publishers and journals providing vague guidelines for when and how to dispute editors’ decisions (1, 2).

This lawlessness makes the world of academic appeals an interesting place. In my own experience, I spent a long time not knowing that I even had the option to appeal. But as my career has progressed, I’ve realized that not only is appealing an option, but it’s an option that (apparently) some people use quite a bit. One friend of mine told me that his supervisor had a paper rejected from a high-impact journal, appealed the decision, and eventually got the paper accepted in that journal. Another time, a journal editor mentioned in passing that, in their experience, most authors never appealed, but some authors appealed all of the time.

Even after I learned that appealing was an option, I still saw it as a bit of a shit thing to do. After all, you’re implying that the editor and/or reviewers got things so wrong that the editor’s decision was unjustified. Then, you’re imposing a cost on them by making them re-evaluate your paper. Part of my feeling also stemmed from a thought that went something like “ok, I know that authors can technically appeal decisions, but basically nobody ever does this right?”. At that time, the idea that I would ever consider appealing a rejection wasn’t even on my radar.

Then, it happened. My collaborators and I had written a paper where we applied signaling theory to the publication process. The idea was interesting and generated some useful insights about how to prevent authors from misleading journals about the quality of their work (that is, how to ensure “honest signaling” in academic publishing). We decided to try our luck and submitted our paper to a high-impact interdisciplinary journal in the social sciences.

So, the paper goes out to review. The reviews are a mixed bag. The editor gives us a chance to revise. We revise and resubmit. The editor says that the revised version is inadequate. We revise and resubmit again. The paper goes back out to review. Two reviewers recommend acceptance. The third reviewer is MIA and the editor has to find another reviewer. The new reviewer points out some potential issues and says that our idea “isn’t really new”. Then comes an email from the editor:

I regret that we cannot offer to publish your manuscript in……

“Fuckkkkkkk, are you kidding me?! These idiots! They didn’t understand the paper at all! Why did I choose this career?!”

This sucked. Eight months had passed between our initial submission and the rejection. We had invested so much time to address the editor’s and reviewers’ comments. And, at least from my perspective, the reviewer’s comments could have been easily addressed or had missed the point. And I didn’t want to restart the whole submission process again at another journal. And I wanted a high-impact publication. So, it’s maybe not surprising that the thought crossed my mind: appeal this shit.

As I was considering the appeal, I had a conversation with a well-established senior scientist about our paper. This was a person whom I had tremendous respect for — someone who had made timeless contributions and continues to be an inspiration to myself and many others. The conversation went something like this:

Senior scientist: Did you appeal?

Me: Haven’t yet and have never done so. Is this a reasonable thing to do?

Senior scientist: No, it’s an asshole thing to do. But you should do it anyway. Plenty of other people do.

Me: Really?

Senior scientist: Yes.

Me: I thought it was a rare asshole defector strategy.

Senior scientist: I would certainly appeal. Well, I hate it as an editor. I apply the sports challenge rule. If they can provide evidence (i.e., the replay) that demonstrates a conclusive error, I’ll overturn the decision. Otherwise the original decision stands.

“You should do it anyway — plenty of other people do”. Shows how much I knew.

I also discussed the situation with a few colleagues. One person, again, someone whom I have tremendous respect for, said something along the lines of “I would never appeal, on principle — it’s dishonorable”.

So, naturally, I appealed. No worries — I never had any honor to begin with.

The consequences of living in the wild west of appeals

My appeal didn’t work out. The editor read my rebuttal, carefully considered my arguments, and then, in so many words, politely told me to piss off.

But going through this process made me wonder: what are the consequences of having an appeals system in which there are no rules, no transparency, and where people don’t agree about whether appealing a rejection is justifiable or worth doing? (Article that argues that appealing is always worthwhile; rebuttal that argues it’s never worthwhile).

Nobody really knows, because we don’t have data on this stuff. I suspect that journal editors have a better sense for this, because they’re the ones who see appeals in action. Off the top of my head though, I see a few big, related issues:

- Exacerbated inequalities between male and female scholars.

- Exacerbated inequalities between senior and junior scholars.

Relative to women, men are (on average) more assertive, overconfident, and willing to take risks (one review of studies). So, all else equal, I bet that men are more likely to think that an editor made a mistake and are more willing to act on this belief by pushing back against an editor’s decision.

Relative to junior scholars, senior scholars have higher status and are better connected within the academic community. So, all else equal, a senior scholar has more “muscle” that they can leverage when appealing. I can imagine journal editors trading off the consequences of reversing their decision and publishing a “meh” paper versus pissing off a powerful, established scholar (see Simine Vazire’s recent article for an example of how this happens). There’s also some evidence that people with higher social status feel more entitled, place more value on their own welfare versus the welfare of others, and are more likely to violate social rules like cutting off other drivers at intersections (one set of studies). And there’s suggestive data that in professional tennis, the highest-ranking players are the ones who are most likely to challenge a call (and because they are so eager to challenge, their challenges are often wrong).

I expect that similar dynamics would play out for scholars from various minority groups, such as ethnic or racial minorities.

Where to from here?

I’m not going to claim that I have a magical solution for how to deal with appeals in academic publishing, but I do hope that this post stimulates a serious discussion about the issue. I mean, it’s a bit embarrassing that many professional sports have their shit together more than we scientists do, at least in this domain.

The good news is that we can look to professional sports for inspiration about how to improve the system of appeals in science. Besides, you know, actually having rules, one thing that strikes me is that we need more transparency. For example, in professional tennis, the Hawk-Eye instant replay system allows everyone — players, umpires, and audience members — to see where a ball landed, whether an umpire’s call was correct, and whether a player’s challenge was justified. So, if an umpire sucks at making calls, or if a player is an asshole and makes repeated unjustifiable challenges, everyone knows.

Appeals in academic publishing could benefit from this level of transparency. As a first step towards this goal, I’ll make my appeal openly available on my website, alongside the published paper. I’ll also do this for all future appeals. After all, as some smart person once said, sunlight is the best disinfectant, and the world of academic appeals is looking a little pale.

If the appeal is against celebrity scientists, usually the editors will not reason with you.