This blog post is going to argue that science would profit if we all suffered more (not less!) from impostor syndrome. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence arguments, so bear with me while I unleash psychology’s second most powerful theoretical tool: the four-fold table.[1]Not to be confused with a camping tool of medium powerfulness, the four-legged folding table.

Table 1

Theoretically Sound Multi-Dimensional Classification of Types of Impostor Syndromes With Examples

| cognitive | emotional | |

| absolute | “Maybe I am not competent enough to research topic X” | Nagging feeling that you do not belong into research |

| relative | “Everybody else here has more skills than I do” | Nagging feeling that somebody else would be a better fit to do the job |

Now, staying with academic traditions, let’s backpedal a bit: The claim is going to be that we need more quadrant I (Absolute Cognitive Impostor Syndrome, or ACIS), and that increasing quadrant I might naturally decrease the number of people who are struggling with the other, overall less desirable types of impostor syndrome which can be found in quadrant II (AEIS), quadrant III (RCIS), and quadrant IV (REIS).[2]All of these are pronounced exactly the way they’re spelled, but with a strong German accent.

Quadrant I: Absolute Cognitive Impostor Syndrome, the thing you need

Objectively speaking, it is extremely likely that you (a) lack some skills that would turn you into a better researcher and (b) lack knowledge about certain things that would be relevant to your line of research. Now maybe you’re an eminent knowledgeable researcher who knows their research field like the insides of their vest pocket, but just think about all the things you don’t know or can’t do properly:

- metaphors: I don’t know if it’s just me, but who actually knows the insides of their vest pockets that well?[3]another weakness, rhetoric devices: ACTUALLY “like the insides of their vest pockets” is a simile, not a metaphor. Ok, seriously now:

- stats: Let’s be frank, most psychologists are not properly prepared to understand the statistical methods that are commonly used within the field. For example, consider principal component analysis, a method I was taught when I was an undergrad: Your smart calculation device estimates a covariance matrix and then calculates the eigenvalues and the corresponding eigenvectors. An eigenvector of a matrix is a vector that changes only by a scalar factor (the eigenvalue) when it is (matrix-)multiplied from left with said matrix. If you think “Well duh, of course that’s how you reduce the dimensionality of a data set”, you must have received way more stats/math training than I did, because 6 years later it still looks like freaking magic to me.[4]Pls send help for my upcoming math exam in September, thx. Now, you might say “Why would you need to understand the technical details of stats methods? You just need to be able to apply them!” and maybe that’s true; but I have found that many misapplications of methods stem from a lack of basic knowledge of how the methods actually work.[5]More knowledge about the stats we apply also helps avoiding embarrassing blunders like interpreting a Heywood case on a substantive level In any case, I’m not trying to say everybody should learn math first — I just think we should stay humble when throwing around fancy complex models we don’t quite understand.

- technical details: Another thing to be frank about, many psychologists happily use measures and fancy high tech that they don’t quite understand. Random example, heart rate variability. There is a whole field of science behind this physiological measure, but somehow, many psychologists don’t care too much about the details, which has sad consequences. Or consider the matter of shooting laser beams on pregnant women’s bellies: It sounds like a great idea to study face perception in fetuses, but once you work out the physics behind it, it is probably not that easy (preprint). Of course, there’s always the option to team up with an expert from another field — which is actually a pretty good way to instill some scientific humility.

- history of ideas: Think you know all theories that have been brought up in the context of your research object? Well, think again. Once I started reading up on well-being research, I got the impression that pretty much every new hip “theory”[6]Read: Mostly boxes connected with arrows is a sad copy of something that has been expressed before by ye olde Greek philosophers. Now you don’t need to read the complete works of Aristotle,[7]2512 pages according to Amazon. but if you feel like your extraordinary intellect just came up with something so profound that it certainly needs to go down in history, maybe check first whether it already went down into history under somebody else’s name. Or maybe save the time and just assume that somebody probably had the idea before—but write about it anyway because if it’s a good idea, it’s a good idea; no matter whether you came up with it or not.[8]For example, the main point of this blog post might be considered a knock-off, but hey, if that Socrates guy was so smart, why didn’t he write shit down?

- your tiny little box: But let’s assume that you have intimate knowledge of the models common in your field (e.g., dynamic continuous time multilevel latent-growth curves); you got a degree in physiology just to make sure that you interpret them signals properly; took philosophy classes to make sure you understood the ontological status of your latent variables; you read everything relevant that has ever been published about your research object. That still doesn’t mean that you have all the equipment you need to do the best possible research, because — surprise! — there could be other highly relevant research fields (sociology, economics, biology, linguistics…) that have something to say about your research object and exactly the methods you would need to gain better insights. Please don’t tell me that you have mastered them as well.

TL;DR: There’s a good chance that you do, in fact, know very little.

Quadrant III: Relative Cognitive Impostor Syndrome, ain’t nobody got time for that

Of course, in many cases, you will probably not compare your level of skills and your knowledge to some abstract ideal, but rather to other people in the field; preferably of those with the same degree of scientific seniority. What if you think that you are simply not as good as the other grad students/postdocs/professors?

First of all, there will of course always be somebody who is better than you. Second, there will also always be a lot of people who are less skillful and less knowledgeable than you. Chances are, if you are reflecting on where exactly you rank among the hypothetical population of all of your peers, you are probably not in the bottom half: It takes quite a bit of understanding of a field to understand that you understand comparatively little. In other words, you are probably good.

But what about gender issues?

More often than not, when the topic of impostor syndrome comes up, it’s about how we need to empower women to get over it.[9]I am aware that people also bring up this issue in the context of POC and first generation students. I can’t talk much about either issue because (1) my experiences as a POC in academia are limited to Germany and I’m well aware that most readers will probably be more interested in the US situation which is probably completely different (2) I’m not a first generation student. The reasoning goes something like this: women are more likely to feel like impostors, hence not presenting themselves well enough/refusing offers that would improve their career prospects/selling themselves under value, hence they are less successful. Thus, we need to fix them to unleash their true beautiful confident independent selves.

Now, it seems pretty likely to me that women are on average less confident than men. However, I suspect the main reason behind that is that women have more accurately calibrated senses of what they can and what they can’t do; of what they know and what they don’t know. Take a random online commenter who confidently asserts total bullshit — chances are, it’s a man. There might be all sorts of reasons for that into which I don’t want to dive here, but my overall impression is that women are just much better at knowing the limits of their abilities and knowledge.

That is obviously a problem in an environment that heavily emphasizes unconditional self-confidence and self-promotion as desirable traits. If everybody exaggerates their achievements by 50%, and if people are not very good at extracting the signal behind all of these exaggerations, being humble means tough luck. So the preferred solution seems to be that we get everybody to exaggerate.

A few weeks ago, I saw a particularly striking example of that logic on Twitter. Somebody tweeted data on how women self-cite less than men. One commenter asked: “So, what can we do so that women self-cite more frequently?” — as if there was no doubt that this was the proper way to address the imbalance; as if we shouldn’t instead wonder why some more or less eminent male authors write papers that can be condensed to “My work is pretty great (see me, everything I ever published since I was born).”

I’m not happy with that logic. “Sure, men are really good at shouting loud enough to drown out all other voices; how can we make women shout just as loud?” You see the problem with that: First, people who simply cannot shout that loud will never get a chance to shine, even though we can be pretty sure that shouting abilities and valuable insights are not positively correlated. Second, we will all end up with hoarse voices and exhausted, because both shouting and trying to listen to everybody shouting just eats up a lot of mental resources.

Now luckily, science is not just a shouting match. We can extract a signal and figure out who actually got something meaningful to say and who is just distributing hot air. If somebody brags about their extraordinary skills, we can go and check their work. If somebody claims that they’re extraordinarily knowledgeable, we can just go and see what they actually know. Sure, that takes some time and effort, but heck, this is science — if we don’t take the time to verify information, we might as well give up on the whole endeavor. And if we find that somebody simply does not deliver, that should massively decrease their prestige within the community. We need social penalties for shameless and inaccurate self-promotion if we don’t want to screw over the decent people who are not interested in bragging about their impressive achievements or the authenticity of their horse voice imitation they mastered by winning all those shouting matches.[10]Apart from that, the “do as men do, as they are the more successful sex” doctrine is flawed to begin with as it’s confusing correlation (men do X, women don’t) with causation (do more X to become more successful). In Bad Blood, a former employee of the health tech startup Theranos remembers how CEO Elizabeth Holmes at one point forgot to turn on the baritone and ended up talking with a natural-sounding young woman’s voice. Men have deeper voices and are the more prominent startup founders, hence, talking with a deep voice increases your chances of success — just like wearing black turtlenecks will turn you into the next Steve Jobs. Not.

More impostor syndrome == less impostor syndrome

If we tone down the whole self-promotion business, that might also have some other neat side-effects. For example, if people stop exaggerating their skills, there’s suddenly much more authentic information out there for others to re-calibrate their own relative impostor syndrome. Sure, I only have a rudimentary understanding of dynamic continuous time multilevel latent-growth curves,[11]I don’t think that actually exists, but you get the point. but if I know that pretty much nobody really understands them, (1) it’s not going to hurt my self-esteem too much and (2) maybe we can have an open discussion about whether it’s a good idea that everybody and their grandparents and grandchildren apply cryptic methods in their papers.

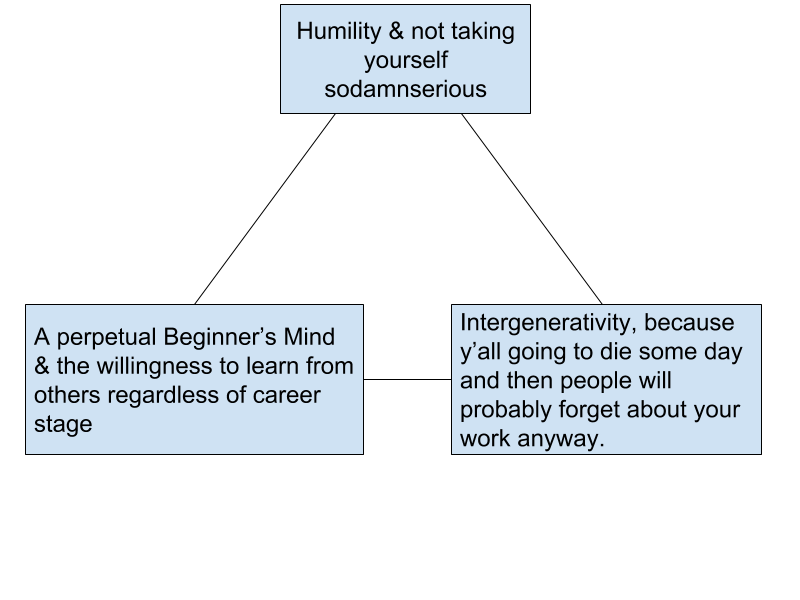

And considering the emotional component of impostor syndrome — the part where you feel like you don’t belong — more humility across all levels of scientific and academic seniority can only help with that. Of course, it’s particularly helpful if the eminent researchers at the top model good behavior, because they’re more influential and can thus do so much more for the emotional well-being of everybody else in the field. Hence, it’s time to finally unleash psychology’s most powerful theoretical tool:

The Triarchic Theory of Non-Toxic Eminence

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Not to be confused with a camping tool of medium powerfulness, the four-legged folding table. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | All of these are pronounced exactly the way they’re spelled, but with a strong German accent. |

| ↑3 | another weakness, rhetoric devices: ACTUALLY “like the insides of their vest pockets” is a simile, not a metaphor. |

| ↑4 | Pls send help for my upcoming math exam in September, thx. |

| ↑5 | More knowledge about the stats we apply also helps avoiding embarrassing blunders like interpreting a Heywood case on a substantive level |

| ↑6 | Read: Mostly boxes connected with arrows |

| ↑7 | 2512 pages according to Amazon. |

| ↑8 | For example, the main point of this blog post might be considered a knock-off, but hey, if that Socrates guy was so smart, why didn’t he write shit down? |

| ↑9 | I am aware that people also bring up this issue in the context of POC and first generation students. I can’t talk much about either issue because (1) my experiences as a POC in academia are limited to Germany and I’m well aware that most readers will probably be more interested in the US situation which is probably completely different (2) I’m not a first generation student. |

| ↑10 | Apart from that, the “do as men do, as they are the more successful sex” doctrine is flawed to begin with as it’s confusing correlation (men do X, women don’t) with causation (do more X to become more successful). In Bad Blood, a former employee of the health tech startup Theranos remembers how CEO Elizabeth Holmes at one point forgot to turn on the baritone and ended up talking with a natural-sounding young woman’s voice. Men have deeper voices and are the more prominent startup founders, hence, talking with a deep voice increases your chances of success — just like wearing black turtlenecks will turn you into the next Steve Jobs. Not. |

| ↑11 | I don’t think that actually exists, but you get the point. |