Expra. Every German psychologist did an Expra during their undergrad, usually in their 2nd or 3rd semester. Expra is short for Experimentalpraktikum[1]See why we need a short word for it? or experimental practical, and is part of the standard curriculum.[2]In some places it is also called Empra, short for Empiriepraktikum, but those places clearly should be set on fire. It is also an initiation rite: You find a small group of peers to collaborate with for 6 months. You come up with a really dorky project name, often a pun on the word Expra.[3]If you think you’re the first to come up with Supercalifragilisticexpralidocious or The Exprandables, think again. Sometimes departments organize an “Expra conference” at the end of the semester, combined with a summer fest or Christmas party to increase attendance and get people drunk so it actually feels like a conference.

For most undergrads, it is the first hands-on empirical study they ever conduct as an experimenter. Next time you meet a German psychologist, go ask them about their Expra — most will have a cherished/romantic/revisionist anecdote to tell (e.g., Malte,[4]Our group attempted to replicate a Stereotype Effect study with four times of the original sample, failed spectacularly, and wondered for the rest of the semester what the original authors had that we did not. Now we live in different times and all know that the answer is flair. Julia,[5]Our Empra (!) consisted of multiple small projects with different labs in which we, e.g., collected data for a small (completely hopeless) social psych study and analyzed EEG data. To be honest, the only thing I really remember is that everybody was obsessing about APA style; so all things considered, I did learn a valuable lesson for my academic career. Ruben,[6]Our group had a poor sap (I drew the longer stick) “accidentally” drop a vibrator and other sex toys out of a Santa Claus bag in the subway, while we “experimentally” varied whether a confederate laughed at him or not. We wanted to test if schadenfreude is contagious, but we learned that Berliners don’t give a shit about anything, and if they do, they immediately suspect a hidden camera. Anne[7] I made the mistake of picking an Empra (!) course offered by the health psychology department. We had to design a questionnaire-based experiment on the influence of descriptive norms on men’s willingness to go to a preventive medical checkup (covered by their health insurance). Me and four other clipboard-armed female undergrads desperately tried to recruit 120 unaccompanied men between 35 and 50 on the freezingly cold streets of Heidelberg and I vowed to never do anything but lab-based infant research ever again. Years later, my desperate attempts to resolve my cognitive dissonance — telling myself that at least trying to get more people to use medical checkups was a good cause — fell apart when I learned that general screenings might do more harm than good.). The less exciting part is that during your undergrad you also have to complete 30 to 40 Versuchspersonenstunden (study subject hours[8]Sometimes also simply “credit points”, but see footnote 2.) in your fellow students’ Expras so they get a decent sample size (20 per condition). I still mumble Stroop sequences in my sleep.

What kind of studies are usually run in Expras? It varies from department to department, teacher to teacher. Some teachers have students select from a range of papers which study they would like to replicate as closely as possible. Others use Expra groups for actual data collection they later include in publications (often uncredited) – I personally have some reservations about either approach, and make the search and selection of both research question and proper operationalizations part of the class.

OMGWTFGDPR

If you haven’t heard of the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) you must not have registered any accounts with any website ever. GDPR[9]It’s actually pronounced Jédeppèr. is an EU law regulating data privacy and protection. Its primary aim is to give EU residents control over their data and increase transparency about who uses them for which purpose. Non-compliance with GDPR can, in theory, have dramatic consequences, with fines going up to €20 million or 4% of the annual turnover[10]At the 100% CI, we’re still deliberating whether we should start selling dank merch, like our branded folding rule, or whether we should retain non-profit status and continue to siphon as much user data as possible. (although public non-profit universities, which in the EU usually have the status of an administrative agency, and their staff, cannot be fined[11]This advice is free. I’m not a lawyer. Don’t @ me.). In practice, the punishment for GDPR violations in publicly funded human subjects research remains to be seen. As far as I know, no university or individual researcher has yet been sued.

Of course these regulations also affect data collected and used for non-profit research, including Expras. GDPR already passed in 2016, yet most people may not even have heard of it until some time around this year’s Towel Day, May 25, on which it became the law of the land. Researchers working with human subject data here at RUB and everywhere else were frantically looking for information on what GDPR meant for their own research.[12]So far: Longer consent forms.

However, the German summer semester starts in April, which means that the Expras had already begun planning their study or even collecting data at that time. A quick, informal survey at our department revealed that the awareness among students of the relevance of GDPR to their project was limited. GDPR had not really been incorporated into any of the research design classes by most of the Expra teachers, but there was also the overarching sense that student projects aren’t “actual science”, so these rules somehow wouldn’t apply. I argue that the following three domains might (or should) be covered in the undergrad curriculum in the context of GDPR.

GDPR-compliant transparency and information

At this department, and I assume at many others as well, a lot of practical wisdom regarding informed consent and participant debriefing gets handed down from cohort to cohort. I briefly checked some old course records, and it appears there is a standard text for consent forms that has neither changed in at least the past 6 years, nor does it differ between Expra groups that study psychological phenomena ranging from working memory to physiological stress responses.

It is obviously fine to withhold some information from study participants about the purpose of the research, and GDPR has not changed that. But under GDPR, participants need to be informed specifically about each type of data processed (e.g., self-report, video material, and yes, the consent form itself). If the data are collected anonymously, and there is no way for the participant to have the data deleted post-collection (which is their right too), then they need to specifically be informed about this as well. The study design might require to provide subjects with this information (and ideally with the opportunity to delete those data right away) post data collection, but not doing so is simply not an option.

GDPR-compliant storage

I don’t have a point estimate, but a large proportion of Expra data is stored in Dropbox (or other commercial cloud services). While Dropbox itself is GDPR compliant, participants are usually not provided with Dropbox’ GDPR privacy guidelines, nor do they usually explicitly consent to the storage on their servers (which is required under GDPR). The point is not that Dropbox servers might be vulnerable (they probably aren’t), but that participants have the right to know where their data is stored, for how long, for which purpose, and who they can contact about this. Don’t even get me started about email.

GDPR-compliant tools

A lot of Expras at RUB use Qualtrics for their data collection. It is quite convenient, not only because it allows digital recording of participant responses, but also assignment to conditions and presentation of stimuli – entire computerized experiments can be run in Qualtrics without any particular requirements other than an Internet connection and a browser. Obviously, the data are stored on Qualtrics’ (GDPR-compliant) servers, so study participants need to be informed about that (see above).

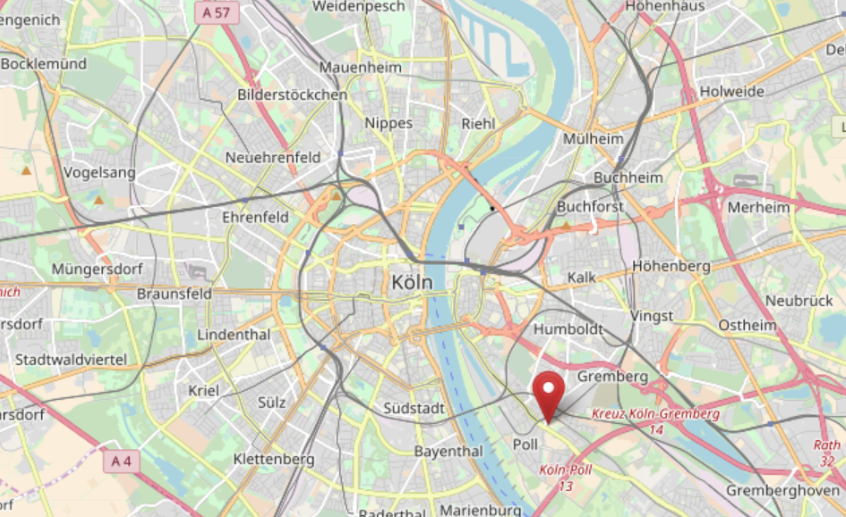

This is not my concern here though: Even when participants are duly informed about data storage, additional, quite personal data may be collected unintentionally by researchers. My very bright Expra group, for example, noticed that Qualtrics by default estimates each respondent’s location with GeoIP. And while it may not be able to tell the exact location of your apartment, it’s only off by a few kilometers.

The location data are stored, but not displayed by default — they have to be made visible in the Data & Analysis > Tools > Choose Columns > Survey Metadata submenu. Recording those data is not disabled by posting the survey with the less-than-ideally named Anonymous Link either, which is somewhat deceptively described as “[a] reusable link that can be pasted into emails or onto a website, and is unable to track identifying information of respondents.” Instead, one has to activate Anonymize Response in the Survey > Survey Options > Survey Termination submenu. Enabling this option is literally flagged as “not recommended.”

I’m not exactly panicking about these observations right now, but I’m not quite comfortable either. Sure, Qualtrics could make those hidden features more transparent, but I do think we need to prepare students to make the right decisions as they collect data. Of course, other privacy laws with data protection regulations have existed before GDPR – and many of the things described above would have violated those regulations as well. With GDPR though, we now have international standards regulating the treatment of participants and their data that allow standardized teaching of data privacy to psychology students in at least 2̶8̶27 countries. Maybe it is time to teach law in the psychology (under)grad curriculum?

Anyway, I know it’s little consolation after all this, but oddly, even though I took a survey, Qualtrics put my GeoIP close to Poll:

Footnotes

| ↑1 | See why we need a short word for it? |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In some places it is also called Empra, short for Empiriepraktikum, but those places clearly should be set on fire. |

| ↑3 | If you think you’re the first to come up with Supercalifragilisticexpralidocious or The Exprandables, think again. |

| ↑4 | Our group attempted to replicate a Stereotype Effect study with four times of the original sample, failed spectacularly, and wondered for the rest of the semester what the original authors had that we did not. Now we live in different times and all know that the answer is flair. |

| ↑5 | Our Empra (!) consisted of multiple small projects with different labs in which we, e.g., collected data for a small (completely hopeless) social psych study and analyzed EEG data. To be honest, the only thing I really remember is that everybody was obsessing about APA style; so all things considered, I did learn a valuable lesson for my academic career. |

| ↑6 | Our group had a poor sap (I drew the longer stick) “accidentally” drop a vibrator and other sex toys out of a Santa Claus bag in the subway, while we “experimentally” varied whether a confederate laughed at him or not. We wanted to test if schadenfreude is contagious, but we learned that Berliners don’t give a shit about anything, and if they do, they immediately suspect a hidden camera. |

| ↑7 | I made the mistake of picking an Empra (!) course offered by the health psychology department. We had to design a questionnaire-based experiment on the influence of descriptive norms on men’s willingness to go to a preventive medical checkup (covered by their health insurance). Me and four other clipboard-armed female undergrads desperately tried to recruit 120 unaccompanied men between 35 and 50 on the freezingly cold streets of Heidelberg and I vowed to never do anything but lab-based infant research ever again. Years later, my desperate attempts to resolve my cognitive dissonance — telling myself that at least trying to get more people to use medical checkups was a good cause — fell apart when I learned that general screenings might do more harm than good. |

| ↑8 | Sometimes also simply “credit points”, but see footnote 2. |

| ↑9 | It’s actually pronounced Jédeppèr. |

| ↑10 | At the 100% CI, we’re still deliberating whether we should start selling dank merch, like our branded folding rule, or whether we should retain non-profit status and continue to siphon as much user data as possible. |

| ↑11 | This advice is free. I’m not a lawyer. Don’t @ me. |

| ↑12 | So far: Longer consent forms. |